Central Asia’s arid climate presents a severe challenge for water management, and historically, inefficient irrigation practices have exacerbated water wastage in the region. Now, the construction of the Qosh Tepa Canal by the Taliban in the Amu Darya Valley threatens to worsen the situation. Once completed, this canal could divert up to 20% of the river’s flow, potentially leading to severe water shortages in Uzbekistan. Additionally, the project may be leveraged by the Taliban as a tool for political pressure, complicating regional water diplomacy.

Will the Qosh Tepa Canal Impact Central Asia’s Water?

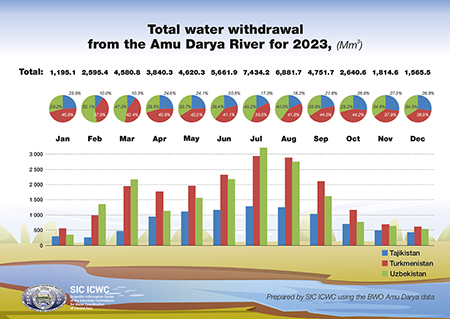

The Amu Darya River, a crucial water source in Central Asia, primarily flows through Tajikistan and Afghanistan, also supplying Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan downstream. In 2023, the water distribution from the Amudarya was as follows: Turkmenistan received 20 cubic kilometers (km³), Uzbekistan 18.3 km³, and Tajikistan 9.4 km³, totaling 47.6 km³. Afghanistan reported using 6% of the river’s flow annually.

The river’s water is generated from precipitation and glacier melt. During dry years, its volume can drop to 34 km³. The Taliban plans to divert 10 km³ annually through the under-construction Qosh Tepa Canal, which represents about 20% of the river’s flow.

However, the exact amount of water diverted during low-flow periods is uncertain. Afghanistan has not signed the UN Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes, and no agreement exists between Afghanistan and Central Asian countries regarding Amu Darya water distribution. This lack of regulation gives Afghanistan considerable leverage over the river’s flow.

Afghanistan’s terrain is predominantly mountainous, but the Qosh Tepa Canal runs through its arid plains. It is reported that the canal is being constructed using outdated methods without proper lining, leading to significant water loss through seepage. Experts predict that climate change will further reduce the Amu Darya’s flow over the next 20 years.

If the Qosh Tepa Canal is completed, Uzbekistan could face a 15% reduction in its water supply from the Amu Darya, leading to potential shortages in Khorezm, Bukhara, Surkhandarya, Navoi regions, and Karakalpakstan. Turkmenistan would also face challenges, with its share of Amu Darya water potentially dropping from 80% to 65%.

To address these issues, a formal agreement on water distribution that includes Afghanistan is essential. This requires recognizing the Taliban as the official government of Afghanistan and engaging in negotiations to establish a fair water-sharing framework.

Political Leverage or Regional Water Crisis?

On August 15, 2021, the Taliban took control of Afghanistan, and since then, no country has officially recognized their government. Seven months after seizing power, in March 2022, the Taliban began constructing the Qosh Tepa Canal, intended to divert significant volumes of water from the Amu Darya River.

The Qosh Tepa Canal will be 285 kilometers long, 100 meters wide, and 8.5 meters deep. It will channel water from the Amu Darya’s Balkh region through Juzjan to Faryab. The canal is planned to be completed in three phases, with the second phase—177 kilometers long—currently 58% finished. The project employs 5,500 workers and 3,300 pieces of equipment, with a completion timeline of five years.

Analysts suggest the rapid construction reflects the Taliban’s intent to demonstrate their capabilities to the international community and potentially use the canal as leverage in political negotiations. There is concern that the canal might be employed to exert pressure on neighboring countries, possibly as a bargaining tool for gaining official recognition.

Political scientist Oybek Sirojov has speculated that external forces might be behind the Qosh Tepa project, investing about one billion dollars to create a regional issue they can mediate. This would suggest that political motives outweigh economic interests. He notes that the canal’s construction contradicts the principles of rational water use, further complicating the situation.

Suhrob Boronov, another political analyst, believes the canal’s swift development indicates its political nature. He warns that water could become as valuable as oil, heightening regional tensions and possibly exacerbating conflicts among the downstream countries.

Sirojov also predicts that significant water diversion could lead to disputes between neighboring countries, potentially fostering both division and integration within the region. Improved water management technologies could save up to 56% of water, emphasizing the need for regional cooperation.

The Economist forecasts that the Qosh Tepa Canal’s completion might intensify regional conflicts and worsen relations over water resources. With climate change already reducing Uzbekistan’s water supply by 15%, additional losses from the canal could exacerbate the situation, potentially causing a 25% reduction in Uzbekistan’s water availability.

Despite Taliban assurances that Uzbekistan will not face water shortages, concerns persist due to the absence of a formal agreement on water usage. President Shavkat Mirziyoyev has expressed worries about the canal fundamentally altering the water balance in Central Asia, highlighting the need for a clear and binding agreement.

Experts also anticipate that the canal could lead to increased water prices in the region and affect water supply to Uzbekistan. The Taliban claims the canal will boost Afghanistan’s economy by irrigating 550,000 hectares and creating 250,000 jobs, with expected annual revenues of $470mn-550mn. However, until a formal agreement is reached, concerns about the canal’s impact on regional water resources remain unresolved.

In March 2023, Afghan Prime Minister Abdul Ghani Baradar assured that the canal would not infringe on neighboring countries’ water rights, but doubts continue until an official contract is signed.

Central Asia’s Water Crisis: Climate Change and Inefficient Use

Central Asia is grappling with a severe water crisis exacerbated by climate change. Large rivers, including the Amu Darya, are shrinking, further stressed by projects like the Qosh Tepa Canal and the Rogun Hydropower Plant in Tajikistan, which divert significant volumes of water.

Despite the growing awareness of water scarcity, Central Asian countries continue to practice inefficient water usage. Traditional flood irrigation methods persist, and modern, water-saving technologies are not widely implemented. Many canals remain unlined, leading to substantial water loss through seepage.

In Turkmenistan, which has the smallest population in the region (7mn), water management inefficiencies are particularly pronounced. Although Turkmenistan receives the most water from the Amudarya, it frequently faces shortages due to outdated irrigation systems and inadequate agricultural expertise. This inefficiency results in substantial water loss in the country’s canals.

Uzbekistan, with 90% of its fresh water used for agriculture, also suffers from ineffective irrigation systems. Water consumption per hectare is 2-2.5 times higher than in technologically advanced countries. The country relies heavily on traditional irrigation methods, with 70% of cultivated areas irrigated this way and 60% of canals being earthen. As a result, a significant portion of the 40 cubic kilometers of water used annually simply seeps into the ground. Although some fields use drip irrigation, many still suffer from inefficient water use.

Climatologist Erkin Abdulahatov has highlighted the urgency of addressing these issues. He points out that the Zarafshan River, which once flowed into the Amu Darya, now barely reaches beyond Navoi due to reduced flow. The Amu Darya could face a similar fate if current practices persist. Abdulahatov recommends transitioning from drip to sprinkler irrigation and privatizing land to encourage farmers to invest in long-term improvements rather than short-term gains.

The Qosh Tepa Canal’s construction adds to Uzbekistan’s concerns, given the existing severe water management problems. As the region faces escalating water challenges, the need for efficient water use and international cooperation becomes increasingly critical.

Amudarya Water: Need for Regional Cooperation and Sustainability

It is crucial to establish a formal agreement with the Taliban regarding the allocation of Amudarya water based on specific limits. This requires proposing actionable measures. Experts suggest that regional countries could collaborate technically and financially with Afghanistan on the Koshtepa canal project, which would facilitate a broader water agreement.

In recent years, Uzbekistan has intensified negotiations with the Taliban, offering cooperation on various fronts. These include the construction of a cement factory in Afghanistan, irrigation projects to enhance the Qosh Tepa Canal, and coal-based electricity production. However, while Afghanistan provides transparent updates on mutual agreements and discussions, Uzbekistan’s stance remains less clear.

Experts recommend that Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan adopt sustainable agricultural practices, such as:

- Diversification of crop types

- Introduction of drip irrigation

- Reuse of collector-drainage waters

According to Erkin Abdulahatov, transitioning Afghanistan’s irrigation systems to drip or rain-based methods could reduce their water requirements from 10 cubic kilometers to 3 cubic kilometers. He suggests that Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan should assist Afghanistan in implementing modern irrigation technologies to ensure effective water management and stability.

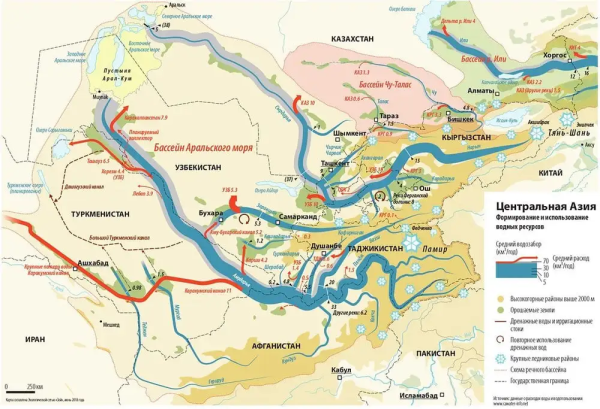

Geographically, Central Asia presents a dichotomy: Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan are in plains, while Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are in mountainous regions. Plains areas are rich in gas resources, whereas mountainous regions have ample water. To address water shortages in the middle and lower reaches of the Amu Darya, several solutions could be considered, including a long-term policy for exchanging gas, electricity, and water between countries. For Uzbekistan, this involves leveraging natural gas resources.

Abdulahatov proposes that Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan should collaborate to establish a stable winter export of affordable electricity to Afghanistan and Tajikistan through existing natural gas-powered generation. Tajikistan could use this electricity to fill the Rogun and Nurek reservoirs in the Amu Darya basin. During the summer, Tajikistan could then power its hydroelectric plants and export electricity to Uzbekistan and Afghanistan at a higher price, ensuring Amu Darya’s flow during the irrigation season. This strategy could also benefit Turkmenistan by allowing it to conserve gas resources and reduce reliance on thermal power plants during the summer.

The water shortage issue in Central Asia is becoming increasingly severe. Experts project that water demand in the region will triple by 2040, potentially causing economic damage equivalent to 11% of the regional GDP. Currently, the UN estimates that the region loses up to $2bn annually due to inefficient water use and shortages.