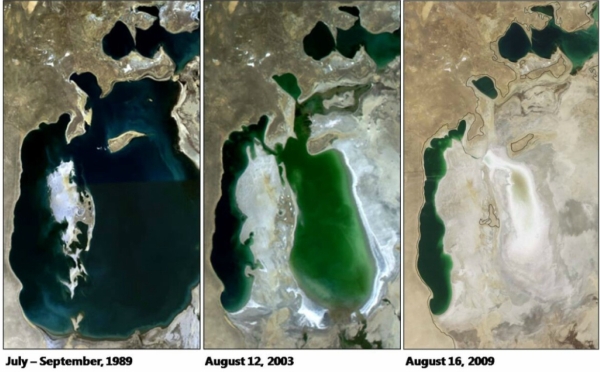

The demand for cotton is often cited as a driving force behind Tsarist Russia’s conquest of Turkestan, as it was essential for producing gunpowder. With neighboring regions deemed unsuitable for cotton cultivation, Uzbekistan became a key “white gold” plantation. This shift led to severe environmental consequences, including the drying up of the Aral Sea, widespread health issues, ecological degradation, and unresolved challenges that continue to affect future generations. This article explores the origins of the cotton policy, its lasting impact, and the ongoing repercussions.

Was Uzbekistan a victim of the USSR’s cotton policy?

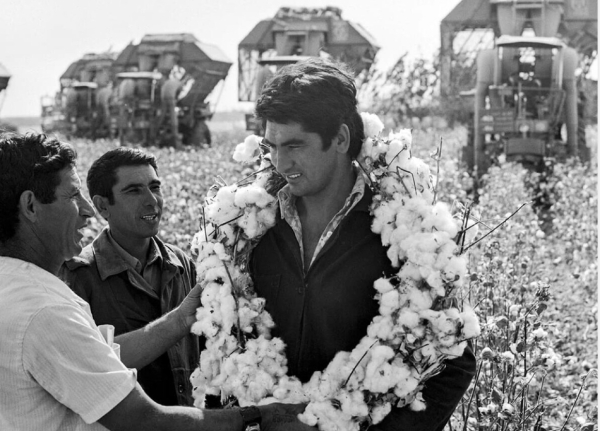

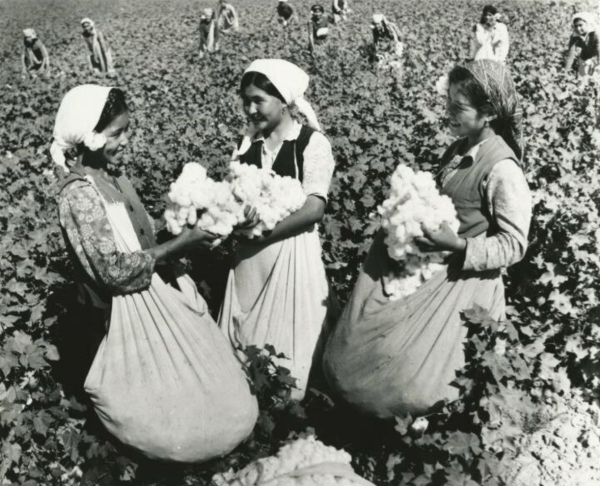

As this year’s cotton harvest season comes to a end in Uzbekistan, the cultivation of “white gold” is no longer what it once was. Today, residents willingly work in the fields for good pay, a stark contrast to the past when teachers, healthcare workers, and other social employees were forced into cotton picking for months. Propaganda portrayed the labor as a patriotic duty, compelling many to participate.

Until 1991, cotton plantations covered 98% of the country’s arable land, stretching over more than 2mn hectares. Uzbekistan produced 4.5mn tons of raw cotton annually, accounting for more than 60% of the USSR’s total cotton output. The harvest season saw 2.5-3mn people working in the fields.

Dr. Feruza Izzat, a historian with a PhD in philosophy, explains the deep-rooted reasons behind cotton’s significance during the Soviet era.

“Cotton was essential for industries like textiles. But it wasn’t just about fabric. During the USSR, cotton was also used to produce gunpowder for ammunition. Cotton powder was a key raw material for the Soviet military. There may have been efforts to project to the West that the Soviet Union was producing vast amounts of cotton, as if the more cotton they grew, the more gunpowder they could produce,” the researcher notes.

In her analysis, Feruza Izzat delves into the escalation of Uzbekistan’s cotton production targets. She highlights a pivotal moment in 1974 when Uzbekistan exceeded its cotton “plan” by producing 5mn tons, far surpassing the original target of 1.5mn tons. Favorable weather conditions contributed to the bumper harvest, and the surplus led to an increased demand for cotton. As a result, the country’s leadership was instructed to sustain this level of production, aiming for 5mn tons annually.

Historian Ikhtiyor Esonov argues that the plan to transform Turkestan into a vast cotton plantation originated not during the Soviet era, but under Tsarist Russia. He asserts that this agricultural strategy played a pivotal role in the Russian Empire’s conquest of the Khanates of Bukhara, Kokand, and Khiva.

“In the 1860s, Tsarist Russia faced an urgent need for cotton. By the late 19th century, following difficulties with sourcing and transporting American cotton, the Russian Empire set its sights on conquering Turkestan to establish local cotton cultivation. The plan was for Turkestan to become Russia’s cotton base—a strategy that originated not just in the Soviet era but also under Tsarist rule. Historically, our ancestors were not cotton cultivators; they focused on gardening and agriculture.

When Uzbekistan became a socialist republic in 1924, it began to transform into the USSR’s primary cotton hub. By 1938, both rural and urban residents were increasingly involved in cotton cultivation. By the 1980s, cotton represented 65 percent of the country’s GDP. This heavy reliance on cotton left the nation unable to function without it. However, only 10 percent of the cotton was processed domestically—most of it was exported as raw material, without any further value-added processing,” explains the expert.

Political scientist Suhrob Boranov, in an interview with Daryo, recalled a letter sent by Turkestan Governor-General Von Kaufmann to Russian Emperor Alexander II in November 1872.

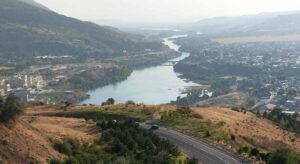

“In this letter, Kaufmann wrote: ‘We must act in such a way that the waters of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers do not reach the Aral Sea. These rivers must be used to irrigate cotton fields, depleting the waters down to the last drop. As the river waters seep into the cotton fields, the Aral Sea will soon dry up. Then we will divert Siberian rivers to refill the Sea. This is the only way to ensure Turkestan’s permanent dependence on Russia,'” says Boranov. The contents of this letter, he notes, foreshadowed the devastating fate of the Aral Sea.

President Shavkat Mirziyoyev addressed the impact of the cotton policy during a speech at the event marking Uzbekistan’s 32nd anniversary of independence.

“The reign of cotton was a disaster for the Uzbek people. This policy dried up the Aral Sea, pushed our ecology to the brink of collapse, and devastated our economy and education system. As a result, several generations grew up without proper education, and we are still grappling with its consequences,” he stated.

The president emphasized the positive changes brought by recent reforms, saying,

“Today, market economy principles have been implemented in cotton cultivation, and the industry has found its rightful place. Teachers have returned to schools, doctors to hospitals, and entrepreneurs have been freed from the burdens of cotton ‘tribute.’ Forced and child labor have been abolished. Uzbekistan has also been removed from international blacklists.”

What did the cotton policy lead to?

The cotton policy in Uzbekistan led to several consequences, particularly the forced labor of the population. After the country gained independence, the first administration continued many Soviet-era practices, including the forced labor of schoolchildren, bank employees, doctors, and other groups during the cotton harvest. This practice persisted for years, despite its harmful impact on the population.

In response to the question about why the parliament didn’t intervene to stop forced labor at that time, Akmal Saidov, the first deputy chairman of the Legislative Chamber of the Oliy Majlis, explained:

“At that time, cotton was considered a strategic commodity, crucial to Uzbekistan’s economy. Cotton was the main source of foreign currency, generating around $1bn in profit during that period. The economy was heavily reliant on cotton production, and breaking out of that system wasn’t something that could happen overnight.”

He further elaborated, “When the USSR was a unified national economy, Uzbekistan specialized in cotton. The added value of cotton during the Soviet era went to the Baltic states, while we only received raw materials and food for cattle. Unfortunately, our economy became deeply dependent on raw material production, and when currency conversion was closed in 1997, cotton became one of the few products we could sell to earn foreign currency. This is why cotton continued to be emphasized as a key economic driver.”

Saidov acknowledged the complexity of transitioning from a system built around raw materials, highlighting the challenges Uzbekistan faced in diversifying its economy after independence.

Akmal Saidov defended the practice of sending children and students to the cotton fields, highlighting the positive aspects of the socialist period.

“Our greatest achievement during the socialist period was in the field of education. This should not be denied. Education was free, and 98-99% of the population was literate, which was among the highest literacy rates in the world. This achievement was recognized by international organizations,” he argued.

However, historian Ikhtiyor Esonov disagreed with Saidov’s perspective, challenging the narrative that the education system should be seen as a positive outcome of the forced cotton labor.

“They say education was free during the USSR,” Esonov remarked. “But after using people for free labor, they provided them with free education. The Soviet Union profited immensely from cotton production. In the 1970s and 80s, cotton was very expensive on the world market, which led them to ramp up production, yet the workers received only pennies and kopecks for their labor.”

Esonov’s critique emphasizes the exploitative nature of the cotton policy, suggesting that while education was a byproduct, it came at the cost of human labor and suffering.

Akmal Saidov acknowledged the negative effects of the cotton policy on the status of teachers in Uzbekistan, admitting,

“We became fans of the hobbyist Hojiboy Tojiboyev, who famously said that if a tractor driver comes while a teacher is resting, the teacher should be sent out. What does this mean? Even Amir Temur left a will saying, ‘If I die, bury me at the feet of my teacher.’ This shows how much respect teachers and education held in the past. Unfortunately, we still cannot raise the respect for teachers to an ideal level. Changing social consciousness is not something that happens overnight.”

In contrast, historian Ikhtiyor Esonov highlighted the devastating consequences of the cotton policy. He argued that it created a lasting “spirit of slavery” within the nation.

“Until now, we cannot escape its influence,” he said, drawing a parallel with the American practice of enslaving Africans. “The colonizers enslaved our people through the cotton policy so masterfully that our ancestors did not even realize their enslavement.”

Esonov also pointed out the environmental and health impacts of cotton cultivation, noting that poisonous chemicals were sprayed during the harvest, affecting the population’s health and gene pool.

“Many people died in their 40s and 50s from various diseases. Cotton poisoned not only the earth, but our consciousness as well,” he added.

Esonov argued that the cotton policy not only damaged the land, but also stunted the intellectual and emotional growth of the people. He recalled a poignant moment when Canadian farmers visited Uzbekistan and cried after witnessing the damage to the land.

“They said, ‘You have turned the earth into a drug addict. Will the productivity be even less?'”

The environmental consequences, including the drying of the Aral Sea due to inefficient irrigation, were also a direct result of the cotton policy.

“Water was used sparingly, and the socio-economic consequences of Soviet policies directly affected the future of Uzbekistan. The country now finds itself in the midst of a vortex of social problems,” Esonov concluded.

Compulsory cotton picking during independence

Compulsory cotton picking persisted in Uzbekistan even after independence, continuing a practice that had lasted for nearly 80 years. Despite the end of the Soviet era, the belief that “cotton is our national wealth” remained ingrained in the country’s culture, and forced labor, including child labor, continued during the cotton harvest. Public sector employees—such as doctors, teachers, and others receiving state salaries—were compelled to participate in cotton picking.

President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, reflecting on the long-standing impact of this practice, criticized the system during a February 2020 meeting of the State Committee for Geology and Mineral Resources.

“What have we been doing for 20-30 years? We worked with cotton and grain for 6 months. What kind of education can this provide? When I was studying, students were sent to pick cotton from the first of September and returned by December 28. How could we focus on our studies under such conditions?” he lamented.

Mirziyoyev emphasized the detrimental effect on the education system, with students missing vital schooling time to work in the fields. He also pointed out the toll on teachers, who, after the harvest season, would return exhausted and burdened by the anticipation of another year of forced labor.

“Who benefited from this? Not our nation. It brought nothing but hardship and suffering. The work was glorified, yet it only led to damage. Our labor, our lives, were undermined,” he concluded, stressing the lasting harm caused by the forced cotton system.

As a result, in 2009, the international Cotton Campaign coalition announced a boycott of Uzbek cotton harvested using forced labor. For 12 years, 331 global brands and retail companies have committed to boycott Uzbek cotton. Major markets such as the USA, Europe, and Canada were closed for the export of Uzbek cotton.

As a result, the country’s cotton exports dropped significantly, negatively affecting foreign investment, currency earnings, new enterprise creation, job growth, and living standards. It wasn’t until 2017 that the Uzbek government began taking serious steps to eliminate forced labor and end the boycott. This included introducing criminal liability for forced labor, canceling cotton production quotas, and significantly raising wages for cotton pickers.

By the 2021 cotton harvest, forced labor was confirmed to have been abolished, prompting the Cotton Campaign coalition to lift the boycott on Uzbek cotton. Sherzod Kudbiyev, then Minister of Labor and now Chairman of the Tax Committee, explained why forced labor had previously been prevalent:

“If wages were low, no one volunteered to pick cotton, so students and even children were sometimes sent to the fields. The main issue lay with budgetary organizations. Local authorities forced schools, kindergartens, and healthcare facilities to participate. Initially, government buildings would display slogans like ‘Everyone to harvest cotton.’ Fighting forced labor was challenging due to a lack of economic incentives,” he stated.

Will cotton be abandoned?

When President Shavkat Mirziyoyev took office, he committed to reducing cotton cultivation and diversifying agricultural production. In early 2020, after announcing plans to end state orders for cotton and grain, the then Minister of Agriculture, Jamshid Khojayev, stated that governors would no longer handle cotton matters. Following through, the state officially canceled the cotton order in March 2020. However, reports indicate that local officials still interfere in the harvesting process.

Umida Haqnazar, a World Trade Organization legal expert, noted that cotton and grain remain dominant in Uzbekistan, with farmers often compelled to plant these crops even under the cluster system.

For example, in 2023, an official was fined nearly UZS 19mn ($1,485) after a neighborhood head in Kashkadarya threatened to withhold child benefits from those who refused to pick cotton. Inspectors penalized the head without investigating higher authorities behind the mandate.

Despite these efforts, Uzbekistan continues to produce substantial amounts of cotton, with recent annual outputs as follows:

- 2020: 3.8mn tons

- 2021: 3.4mn tons

- 2022: 3.5mn tons

- 2023: 3.7mn tons

Cotton picking is fully automated

Alisher Shukurov, Uzbekistan’s Deputy Minister of Agriculture, reported to Daryo that mechanization in cotton harvesting is advancing rapidly, with much of the 2024 crop already gathered by specialized machines. While some technician shortages remain, the shift to fully automated harvesting is well underway.

To further modernize cotton production, Uzbekistan is expanding water-saving irrigation, covering 100,000 hectares this year and aiming for 400,000 hectares by next year. Cotton will be exclusively irrigated with water-efficient systems, and a new double-row planting method, based on Chinese techniques, has been introduced. This method, used on around 2.5mn hectares in China’s Xinjiang region, is expected to significantly boost yields.

Shukurov highlighted that Uzbekistan’s cotton sector includes 100 clusters and 80,000 farmers, with a growing focus on producing value-added textiles. The nation plans to fully process all cotton domestically by 2025, transitioning from raw cotton exports to finished textile goods. This shift is reflected in the recent data: from January to September 2024, Uzbekistan exported $2.2bn in textiles, accounting for 11.2% of its total exports, a marked change from 1992, when raw cotton made up 90% of exports.