Uzbekistan holds 1.8 trillion cubic meters of gas reserves, yet imports from Russia are on the rise, driving up prices and escalating budgetary costs. Despite a presidential decree mandating an increase in gas production, this goal remains unachieved. This article explores the underlying reasons and the resulting implications.

Uzbekistan’s Shift to Gas Importer Status

On December 5, 2023, a conference on the peaceful use of nuclear energy took place in Samarkand, with a Daryo correspondent in attendance. During his opening speech, Energy Minister Jurabek Mirzamahmudov addressed a critical issue: Uzbekistan’s transition from a gas exporter to an importer.

“In recent years, we have shifted from being a gas-exporting nation to becoming an importer,” he stated. “To address this, it is essential to introduce new energy technologies, and we believe increasing the number of nuclear power plants should be included in our multi-year energy development plans.”

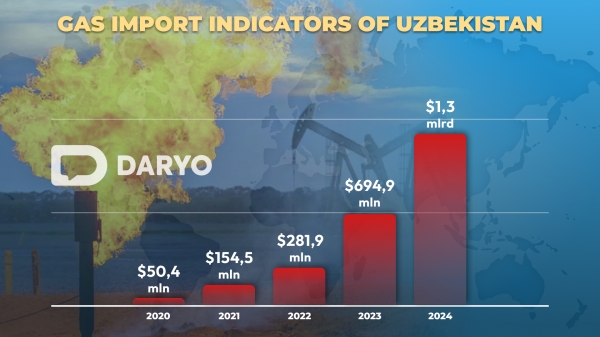

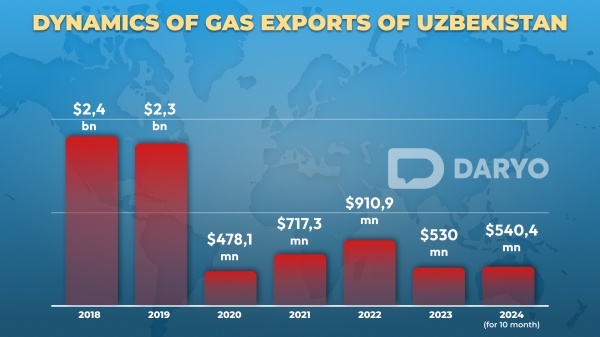

This shift to importer status, as highlighted by Mirzamahmudov, became evident in 2023. Gas imports surged to $694.9mn—2.5 times higher than in previous years—while exports halved to $529.9mn. Until recently, Uzbekistan had been a significant gas exporter to countries like China and Kyrgyzstan.

Comparing the data over recent years reveals the stark change: In 2018, Uzbekistan exported $2.4bn worth of gas, and in 2019, $2.3bn, with no gas imports. However, the trend shifted in 2020, when gas imports began, although exports still outpaced imports until 2023. For example, in 2020, the value of gas exports exceeded imports by $428mn, by $563mn in 2021, and by $629mn in 2022.

By 2024, the share of gas imports has reached a record high. From January to October, Uzbekistan imported gas worth approximately $1.365bn, a 2.4-fold increase compared to the same period in 2023, when imports totaled $561.7mn. This marks the largest volume of gas imports in recent history.

The timing is notable, as winter’s arrival typically drives up gas demand while slowing extraction processes, suggesting that import levels will continue to rise. Fluctuating temperatures quickly impact Uzbekistan’s energy sector. For instance, recent gas restrictions caused long queues at gas stations and price hikes, as greenhouses received less gas than usual.

A gas shortage poses a serious risk to the economy, as 85% of the country’s electricity is generated from gas. It remains unclear whether the Ministry of Economy and Finance or the Ministry of Energy calculates the economic impact of gas and electricity outages on the national budget and citizens, as such information has not been disclosed, nor has compensation been discussed. Despite the shortage, Uzbekistan continues to export gas. In January-October 2024, the country exported gas worth $540mn, slightly more than the $530mn exported in the same period in 2023.

Despite a significant increase in imports, the volume of gas exports remains much lower, confirming that Uzbekistan has transitioned to an importing country. For context, gas exports reached $910.9mn in 2022, compared to $717.3mn in 2021.

Energy Minister Jurabek Mirzamahmudov addressed the issue, explaining why gas exports have not been halted. He emphasized that substantial investments have been made by international partners in gas production and processing.

“A portion of the gas will be exported to cover these costs, but exports will only continue if they do not compromise domestic consumption,” he said. “If domestic demand rises, exports will be suspended. The majority of gas produced in Uzbekistan is allocated to the local market, and any shortfall will be supplemented by imported gas.”

Unfulfilled Presidential Directive

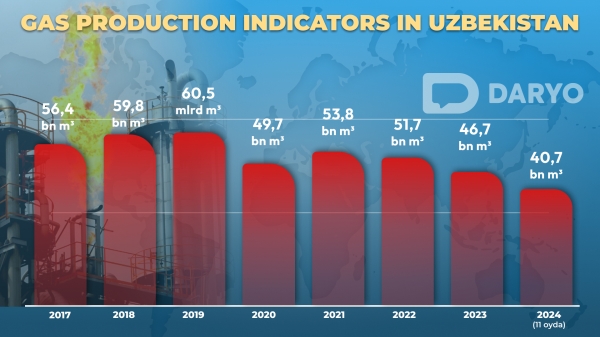

Natural gas production in Uzbekistan has been declining annually. In 2023, the country produced just 46.7bn cubic meters of gas, the lowest output in seven years. This marks a 9.7bn cubic meter decrease from 2017, when production reached 56.4bn cubic meters.

These figures represent the total production from all companies, with Uzbekneftegaz being the largest producer. Notably, over 30% of the gas produced in 2022 was attributed to companies with Russian capital. In that year, Uzbekneftegaz alone produced 32.2bn cubic meters of gas.

In January 2022, a presidential decree outlined a goal to boost gas production to 56.3bn cubic meters by 2022 as part of the “Development Strategy of New Uzbekistan for 2022-2026.” However, this target was not met. In 2022, production was 51.7bn cubic meters—2.1bn cubic meters less than in 2021. The goal was also unmet in 2023, with a significant drop in output that year.

In 2023, the presidential decree “On the Strategy of Uzbekistan – 2030” was signed, setting even more ambitious goals for the country’s energy sector. Among the targets outlined for 2030, one key objective is to increase natural gas production to 62bn cubic meters. However, achieving the 2022 production levels remains uncertain, as the country faces significant challenges.

From January to October 2024, Uzbekistan produced 37.1bn cubic meters of gas, nearly 1.8bn cubic meters less than the same period in 2023. For context, the annual gas consumption of greenhouses across the entire country is approximately 1bn cubic meters, highlighting the scale of the decline in production.

Stopping the Decline: The Critical Goal

Halting the decline in gas production should be the primary focus. Without stabilizing production, it seems unrealistic to consider further improvements. Unfortunately, there are signs that insufficient measures are being taken to address this issue. Energy Minister Jurabek Mirzamahmudov recently pointed out the rising imports of gas, acknowledging the challenges ahead.

“Gas consumption is increasing. Our plan anticipates that by 2030, natural gas imports will reach about 11bn cubic meters. The delay in geological exploration has led to a situation where 85% of our field reserves have been depleted. It takes 3-5 years to develop new fields, so it will take time to reverse this trend,” the minister explained.

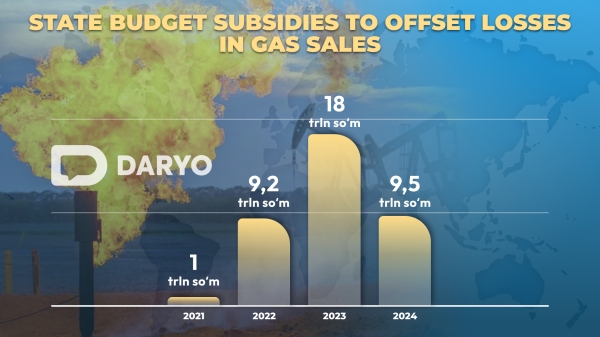

The energy sector continues to receive the largest subsidies from the national budget. In 2023, approximately UZS 18 trillion ($1.4bn) were allocated to compensate for losses from gas sales, as the government covers the gap caused by selling gas at lower prices. This year, the subsidy amount is expected to be UZS 9.5 trillion ($736.3mn), and these funds have already been disbursed. Additionally, large-scale investments are being directed towards increasing gas production under state guarantees, though the results are yet to be seen.

As Minister Mirzamahmudov pointed out, over 80% of the reserves from Uzbekistan’s existing gas fields have already been extracted. He explained that as fields are being penetrated deeper, challenges are emerging, particularly at compression stations, where additional time and costs are required for gas extraction. These challenges have led to an increase in the cost of production.

“No matter how deeply we explore the fields, the results aren’t always as expected. Our outdated equipment has contributed to rising accidents and technical failures,” the minister noted. “Due to delays in modernization, we’ve had to deal with frequent shutdowns of compressor station units, resulting in 333 technical failures in just four months.”

Ulugbek Nazarov, Chairman of Uzlitineftgaz, spoke to a Daryo correspondent about the challenges facing Uzbekistan’s gas industry. He highlighted that the sector has been operational for more than 70 years, with large fields discovered between 1950 and 1970, each holding reserves of 600-700bn cubic meters of gas. Today, however, the size of reserves is diminishing.

“There are currently 300 gas fields in the republic, but their reserves are dwindling. The newly discovered fields contain only 3-4bn cubic meters of gas,” Nazarov said. “As a result, our remaining large field reserves will last 30 to 50 years, but the productivity of new fields is low, meaning that during winter, the demand for gas will outstrip supply.”

Nazarov further emphasized the importance of diversifying energy production, as much of the country’s electricity is generated using gas. He also pointed out that gas in Uzbekistan is cheaper than in many other countries. For instance, Russia sells gas for $90 per thousand cubic meters, while Uzbekistan’s price is between $50 and $60.

“If prices stay at these levels, we risk halting geological exploration, which will lead to even greater imports of gas,” Nazarov warned. “Therefore, increasing gas production is critical to reducing imports.”

Despite efforts to curb gas imports, data shows that the volume of gas purchases from abroad is increasing rapidly. Economist Abdulla Abdukodirov noted that multiple factors have contributed to the current state of the energy sector, highlighting the urgent need for reform and strategic planning to address these challenges.

Despite significant financial allocations to the energy sector, critical shortcomings remain. New gas fields have not been discovered, geological exploration has not been carried out, and existing fields have not been rehabilitated. Instead, the focus has been on large-scale projects that primarily redistribute the gas produced rather than address the need for new reserves. These projects, undertaken between 2017 and 2020, include the construction of the GTL plant and the expansion of the Shurtan gas and chemical complex.

Rather than investing in the exploration of new fields, funds were directed towards projects that burned through existing gas reserves. Moreover, these projects turned out to be costly and unprofitable for the population. The GTL plant, initially proposed in 2017 for $900mn, saw its costs skyrocket to $4.9bn five years later.

“The financing strategy for these projects is fundamentally flawed,” noted the economist who analyzed the issue.

As of August 2023, Uzbekistan holds 1.854 trillion cubic meters of gas reserves across its fields, with half—933bn cubic meters—belonging to Uzbekneftegaz.

Risks of Import Dependency

In October 2023, Uzbekistan began importing gas from Russia, signing an agreement to purchase 9mn cubic meters of gas per day, or 2.8bn cubic meters annually. By 2026, this figure is expected to quadruple, reaching 11bn cubic meters per year. To facilitate this increase, Uztransgaz plans to modernize its main gas pipelines, with $500mn allocated for the first phase of the project, set to run from 2024 to 2030. This effort aims to boost natural gas imports to 32mn cubic meters per day, with the financing sourced from foreign loans.

Economist Otabek Bakirov has raised concerns about the risks associated with growing dependency on gas imports. He warned that declining domestic production could leave Uzbekistan vulnerable in the future.

“If the war with Ukraine ends, Russia is more likely to sell its gas to Western countries, which offer higher prices of $450-500 per thousand cubic meters, rather than selling to us for $150-180. This could leave us dependent on a market that may no longer be willing or able to supply us at these low prices,” Bakirov said.

He cautioned that once Uzbekistan becomes reliant on these imports, finding alternative sources could become extremely difficult. “Currently, Russia is forced to sell its gas to Central Asia and China due to its situation, but this could change,” he noted.

Economist Abdulla Abdukodirov also critiqued the growing reliance on gas imports, arguing that it’s a short-sighted strategy.

“The narrative that Uzbekistan is about to run out of gas is being deliberately pushed to justify increased imports from Russia,” Abdukodirov explained. “We still have ample gas reserves that could last for generations. Becoming dependent on imports now would be a strategic mistake. If not today, then tomorrow we will find ourselves entirely reliant on Russia.”

At a parliamentary session in September, a representative of the Tax Committee revealed the cost of imported gas. Uzbekistan imports 1,000 cubic meters of natural gas at $160, yet the price for the same amount of gas sold to the population and businesses ranges from 480,000 to 1.5mn soums ($37-$116). This means imported gas is sold at a significantly lower price, creating a financial burden on the state budget.

According to the Ministry of Energy in September 2023, the cost of producing 1 cubic meter of gas domestically is UZS 1,890 ($0.15), or UZS 1.890mn ($146) per 1,000 cubic meters. This means that domestically produced gas is being sold well below its cost. In 2024, UZS 9.5 trillion ($736.3mn) will be allocated to cover the losses from both imported gas and domestically produced gas sold at a loss. As demand for gas continues to grow, the volume of imports—and the corresponding subsidies—are expected to increase, further straining the budget.

Analysts argue that the delay in implementing market mechanisms in the energy sector has hindered the system’s development, forcing the state to subsidize a system operating at a loss. These subsidies contribute to the growing budget deficit, limiting funds available for essential social programs and critical investments in the energy sector’s future.

Economist Behzod Hoshimov argues that government subsidies for energy are a direct result of the inefficiency within energy-producing enterprises.

“These enterprises operate inefficiently because they have no real incentive to improve,” he explains. “For example, as an energy producer, when you go to work each day, your only motivation is to work inefficiently, incur higher costs, and avoid making improvements. The system rewards inefficiency. If you show up and say, ‘My expenses are a thousand soums and my production is a hundred soums, pay me the difference,’ the government will cover it. Even if you introduce more efficient technology or streamline operations, there’s no reward for that. The system doesn’t incentivize progress.”

Hoshimov highlights the ongoing “cat-and-mouse” game between energy enterprises and the government.

“Enterprises inflate prices, while the government tries to lower them. In the end, it’s society that pays. The government spends billions on subsidies, and it’s the taxpayers’ money funding this inefficiency,” he says.

The government has raised gas and electricity prices for businesses and organizations as of October 1, 2023, in an effort to transition toward market-based pricing. Further price hikes for consumers are scheduled for 2024, with plans for additional increases in 2025. These moves are part of a strategy to reduce budget expenditures and stimulate sector development, but Hoshimov remains cautious.

“I don’t think that just raising prices will solve everything. The Ministry of Energy and other officials need to clearly tell the public when they plan to achieve a functioning energy market,” he states.

However, the rising energy tariffs will have significant consequences for both consumers and businesses. As energy costs increase, the overall cost of living will rise, driving inflation across the economy.

If energy reform is implemented effectively—ensuring a reliable energy supply for both the population and businesses, while avoiding excessive government spending on the sector—the economy will experience growth and development. However, if prices are simply raised without accompanying reforms, this will only harm the economy in the long run.